A Haitian Child’s First Days in America

Marmarah “Mars” Similien said she didn’t have any expectations of what America would be like because she “wasn’t given a brochure.”

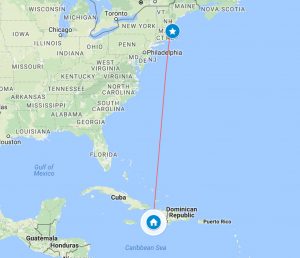

Similien came to America wide-eyed and frightened when she was 5 years old. Three years earlier, her parents and older siblings left her and her twin sister Christina Similien behind in Chantal, Haiti. Her parents wanted to establish a life for their family in Boston, Massachusetts before sending for their young daughters.

When Similien’s parents beckoned for her and her sister to join them in America, she didn’t know what to expect. She threw a tantrum to avoid leaving her Caribbean home, kicking, screaming and holding onto furniture.

“At five, I thought it was going to work but it was just a waste of my time because the tickets were [bought],” Similien said.

Unsuccessful, she and her twin were put on a plane by themselves, heading into the unknown.

When they arrived in Boston, the girls were welcomed by an embrace from their mother’s friend. She took them to their family’s apartment. Waiting for them were the Similien’s relatives. They cheered, embraced them and kissed them on the cheeks, in the traditional Haitian way. Similien remembers going through the motions but feeling nothing but fear. She and Christina stood close to each other like they had been since they arrived at the airport because they were the only ones they knew in this foreign place.

Then another stranger, an even more excited one, pushed through the crowd with tears flowing freely down her face. It was the girls’ mother.

“She was also a stranger in a room full of strangers,” said Similien.

When Similien woke up the next morning, she was still in shock. During her adjustment period, Similien remembers she and Christina would hide in the closet or the bathroom and whisper about plans to escape back to Haiti.

To add to the strangeness of her first days in America, Similien was served Eggo Waffles as her first meal. She had never seen them before.

“I remember [my mom] put this plate of soggy waffles in front of me,” Similien said. “There wasn’t even any syrup on it. It [was] just plain, buttermilk Eggo Waffles.”

She was used to eating heartier meals in Haiti.

“I remember I could not stand the sight of Eggo Waffles, and eventually I loved them,” Similien said. “I have some in my freezer right now. So it’s really funny how things turn out.”

She eats them with a drizzle of syrup and cinnamon butter.

But her next food memory wasn’t disappointing at all. It was ice cream. Similien had ice cream before, but she never had ice cream in a waffle cone.

“What is this thing?” Similien remembers wondering. “Do I eat it after or throw it away?”

As she pondered on what to do with the cone, the ice cream started melting.

“It was this moment of childish amazement, curiosity and wonder,” said Similien, as she recalls lifting up the cone to catch the dripping, sugary goodness like she was playing a game.

Something else that amazed Similien in the U.S. was white people’s hair. She had never seen a white person before. She was dazzled by girls’ hair: blonde, brunette and red. She remembers, in particular, her classmate Jessica’s blonde hair that reminded her of a yellow color pencil.

Those days of amazement were balanced by some days of familiarity. Similien arrived in Boston in August, so she was headed to elementary school. Her first school, which was filled with other immigrants, including Haitians, made her transition a little smoother. She was able to still speak her native French and Creole languages while learning English.

“It was the first space where my parents and my relatives were not in, and it was a space where … it was all a bit more freedom,” Similien said. “During recess—just getting out with the kids and [doing] kid stuff and not [worrying] about this huge change.”

But at Similien’s second elementary school, she did have a few worries. She says the school children, who were mostly white, had never seen someone who looked like her, in the way that she dressed and with the texture of her hair. She was stared at, teased and bullied.

“I didn’t want to be different, and being Haitian made me different,” Similien said. “Having an accent made me different. So I guess I wanted to hide that part for a little bit. I stopped speaking my native language and would just try to assimilate more.”

Now that Similien is 19, she remembers that peer pressure to fit in, but feels more confident as an adult.

She realizes that she doesn’t have the story a lot of immigrant children experience. But looking back on her life she suggests that immigrants, “be open to everything and never feel like they’re losing out on their home.”

“You’ll always be wherever you came from,” Similien said.